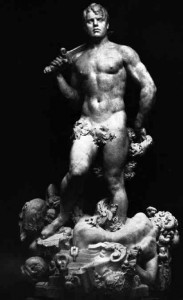

Triumph of Civic Virtue

History

In 1891, Angelina Crane made public bequest of $53,000 to New York City to erect a drinking fountain in her honor. Despite contest from heirs, Ms. Crane’s wish was finally upheld by the courts, and mayor George B. McClellan commissioned Frederick William MacMonnies to design a monument that would stand in City Hall Park. The Piccirilli brothers (who also executed the statue of Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial,) carved the stone.

Although the commission and intended location must have induced MacMonnies to honor the ideals of public service, he apparently had considerable decision-making power over the subject and execution. In his own words,

I had plenty of time and all kinds of ideas. I thought at first I would make a city of New York, a female figure, a creature who was enthroned, and waters and rivers at the side, etc., and then that did not seem to appeal to me, and then I finally thought as I got nearer and nearer, of this idea of local dignity, the genie of the spot—so I thought I would make Civic Virtue.

Although MacMonnies is most commonly associated with the Beaux Arts school, Triumph of Civic Virtue sports a number of features reflect a more purely classical style. The lilt in the man’s stance hearkens back to Michaelangelo’s “David,” for example. “Civic Virtue’s” musculature contains a similar detail and proportion to that of the Farnese Hercules. The female figures of Vice and Corruption hearken back to demigods and monsters of Greek myth.

Even before the statue’s completion, leading up to its 1922 dedication, officials at City Hall had allegedly begun receiving complaints about the nature of the depiction of a man over two women. Depending on the source one follows, objections were lodged by the Federation of Women’s Clubs, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the National League of Women Voters. Feminist groups had begun to be taken more seriously at the time in general, after their suffrage victory with the passage of the Ninetheenth Amendment.

Michele Bogart, an art historian and authority on the Triumph of Civic Virtue, notes that MacMonnies’ depictions of women in public works were already controversial. In her words, his “conflation of the public (municipal) and the personal (psychological) disturbed many people.”

Indeed, in 1894 MacMonnies (an American expatriate who spent much of his life in France,) had travelled back to the United States to dedicate another work, the Bacchante with Infant Faun to the Boston Public Library. It was a gesture of personal gratitude toward its architect Charles Follen McKim.

As with Triumph of Civic Virtue, special interest groups who found the imagery highly offensive to their sensibilities spoke out. McKim was not stalwart against political pressure, and in turn presented it to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It has since become enormously popular, with numerous casts have since made for other museums.

The case of Triumph of Civic Virtue however, took a different turn. New York Mayor John F. Hylan, who probably was not pleased to bear responsibility for the decision made by the city’s Art Commission, held a hearing about its future. It was mayor Fiorello La Guardia who ultimately effected the statue’s removal from City Hall Park. Many sources cite, correctly, that La Guardia objected to the statue on the ground that he did not enjoy seeing its backside on a daily basis. The urgings of an equally displeased Robert Moses however, would undoubtedly have influenced the decision as well.

Triumph of Civic Virtue was originally slated to be moved to Long Island City which was the original borough seat, but came to Kew Gardens in 1941 following the relocation of Borough Hall. Queens borough president George Upton Harvey had come into office after his predecessor resigned due to scandal, and the statue was genuinely courted for its timely allegorical value.

And so the statue has remained to the current day. On its 50th anniversary in 1972, a group from the National Organization of Women protested for the its removal. In 1987 Claire Schulman, Queens’ first female borough president, also called for it to be evicted. Helen Marshall, current sitting borough president as of 2002, has in the past not considered the statue worth actively supporting.

Throughout the decades, the ravages of weather and time have taken their own toll. The Fine Arts Federation of New York took up a campaign to procure the necessary funding to restore the Triumph of Civic Virtue, seeking both private donors and petition the city for abiding by its obligation to maintain public art. The economic downturn of 2008 had a dampening effect on these efforts.

In February 2011, U.S. representative for the district Anthony Weiner along with New York City councilwoman Julissa Ferreras for Queens’ 21st district (who is also Chair of the council’s Committee on Women’s Issues) held a joint press conference in which it was announced that the statue was placed up for sale on the online marketplace Craigslist. Brooklyn’s Green-Wood cemetery expressed interest. (Members of MacMonnies’ family are buried there.) Weiner’s efforts summarily ceased however, after he became embroiled in a sex scandal that forced his resignation from office.

As of July of 2012, the statue’s outcome appears to lie in the hands of the New York’s Department of City Administrative Services (DCAS). The statue was fenced in after receiving reports of a serious crack needing repair. DCAS has released a statement denying that any firm plans have yet been made.

In conclusion, it’s worth nothing that MacMonnies defended his work in his own words as follows:

What do I care if all the ignoramuses and quack politicians in New York, together with all the dam-fool women get together to talk about my statue? Let ’em cackle. Let ’em babble. You can’t change the eternal verities that way. From Paris to Patagonia—universal allegory pictures sirens, temptresses, as woman. If you suppress allegory you suppress all intellectual effort. I gather that allegory has long been extinct in City Hall.